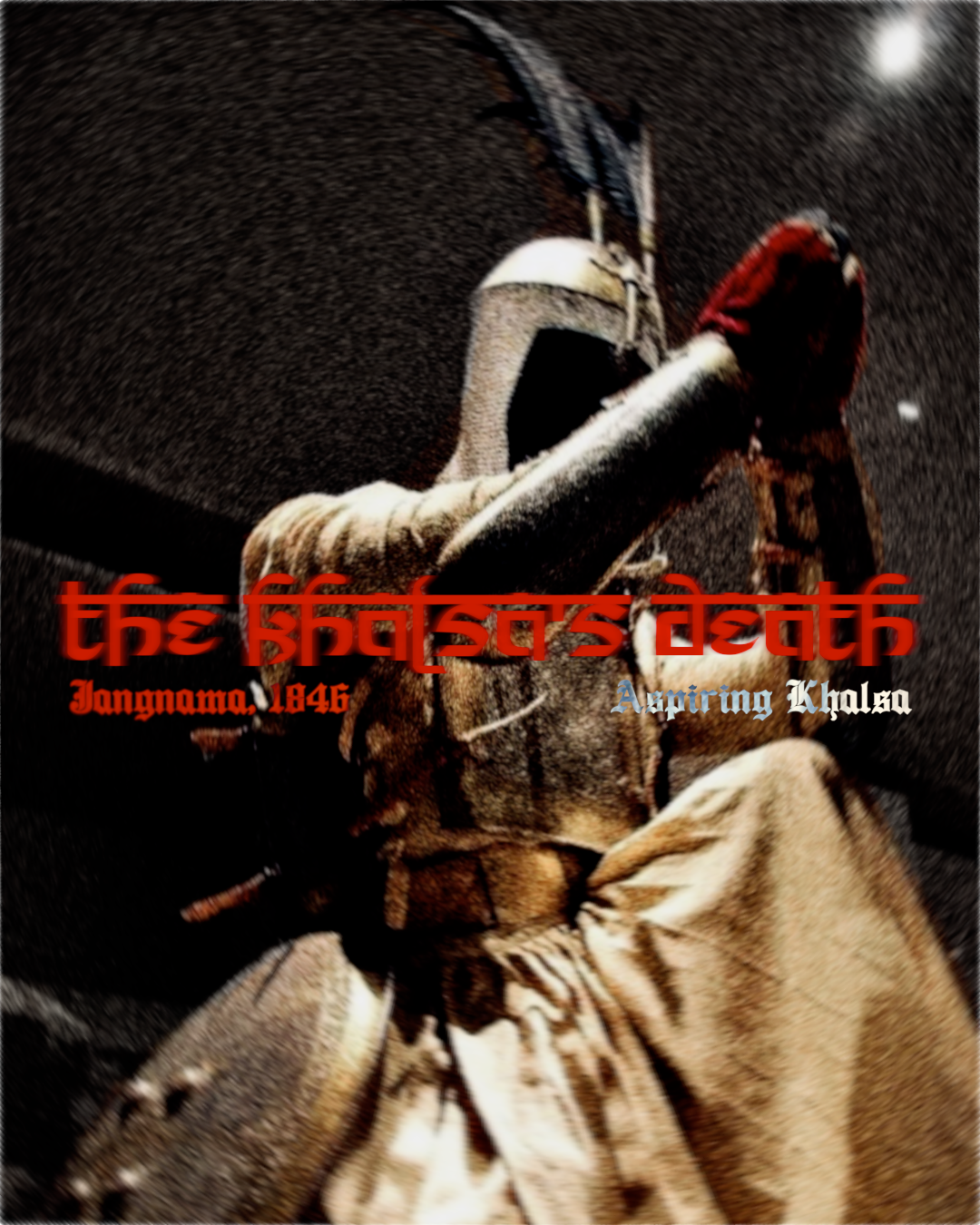

The Khalsa's Death

Shah Muhammad's Jangnama (1846)

Intro

Jangnama, written by Shah Muhammad in 1846, tells the end of the Sikh Empire from the perspective of the Khalsa. Muhammad, who writes after Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s passing, enlightens the reader on the psyche of the Khalsa during this time period and tells of a raging warband which sought to expand their wealth and power.

Early 19th century writer, Rattan Singh Bhangu, who’s grandparents became Khalse under Guru Gobind Singh, describes an earlier Khalsa as hellbent on creating the Raj, having been anointed as sovereigns by the 10th Guru. (Panth Prakash) The British, who witnessed later Sikhs, made similar observations saying that, “the freedom and boldness of the Sikhs could be traced to the traditions of the Khalsa,” and calling them, “the religion of warfare and conquest.” (Sikhs in British Census Reports)

By the time of Jangnama, the 10th Guru’s mission for the Khalsa, ਰਾਜ ਕਰੇਗਾ ਖਾਲਸਾ / Raj Karega Khalsa (the Khalsa will rule, Tankhanama), had been maintained continuously for over 140 years— meaning the Khalsa was either seeking or achieving rule throughout this time. Writers of over this period also make clear that political sovereignty had become seared into their identity. But what happened to the Khalsa and their identity upon experiencing the abrupt fall of their empire? With signs of their fiery psyche extinguishing following the loss in the first Anglo-Sikh war, Jangnama not only recounts a glorious Khalsa, but the Khalsa’s death as well.

Note: Jangnama is a single perspective from this time period. This is not an all encompassing analysis of the First Anglo-Sikh War.

Jangnama

"The Singhs got together and the congregation swore in a Gurmatta [Sarbat Khalsa], 'We shall go and kill the Feringhee [British]. If ever they meet us in the battle, in no time we shall do away with them. We didn't spare the venerable Bhai Bir Singh. Feringhee are simply foredoomed as we never can be defeated. O Shah Mohammed! After making a mince-meat of them at Ludhiana, we shall surely march into Delhi.'" (65)

Administrative nightmare

“For, the real power now lay in the hands of louts, as the rule of jungle replaced the rule of law. The rogues that with impunity can kill the kings, tell me, whose authority shall they ever respect? O Shah Muhammad! The sword was now the sole arbiter and not a single swish of it went without its prey.” (30)

An important takeaway from Shah Muhammad’s account is the failure of Sikh aristocrats after Ranjit Singh’s death. Backstabbing and betrayals were rampant in a battle for the throne, all while a rogue Khalsa army was doing it’s own bidding. Shah Muhammad specifically asserts that Rani Jind Kaur, Ranjit Singh’s youngest wife and mother of Duleep Singh, was the cause the Khalsa’s power crumbling once seizing administrative power. He goes as far to claim that Rani Jind Kaur wished the Khalsa to perish for executing her brother, as well as cooperating with the British before the war.

Interestingly, Muhammad also claims that the British weren’t too keen on direct war with the Sikhs. Given the massive cost both sides would sustain, it could be a reasonable conjecture that such a brutal war was in neither side’s interest prior to fighting.

British message to the Sardars (according to Shah Muhammad)

“Why are you bent upon fighting like this? We had a pact with your late Maharaja. Then why are you now stoking the dying embers? You can take any amount of wealth from us; If you ever wanted more, you would get it. We are determined to defend our interests. Why, for nothing, should you expand so much energy and resources?” (64)

A Hellbent Khalsa

“Wrote back the Singhs to the Feringhee [British]: ‘We are sworn to kill you in open battle. We look at disdain at the money you offer us — even if it be a whole mountain piled up before us. The Panth that conquered Jammu not long ago has now turned up to take you on. O Shah Muhammad! You put your guns in front and send your chosen soldiers to measure swords with us…

Panches [regimental committees] of all the platoons wrote to the ranks: ‘Our armies shall move on the offensive today. We had killed the venerable Bir Singh by using guns. You can see we do not spare even men of God. Didn’t we conquer all the forts around? Didn’t we level the citadels of Bhatinda and Kulu? O Shah Muhammad! That alone shall happen. Which the Panth, in its wisdom, will and decrees.” (65-66)

Jangnama paints quite a war hungry picture of the Khalsa in this response to the British. Reading Muhammad describe the hot-headed nature of the Sardars, one can feel the arrogance and vigor that they possessed. The passage also mentions the Panches, or Panchayets, which were the selected representatives of the each Khalsa regiment. Much of the Khalsa became disillusioned with the aristocracy and began operating with a level of independence through the Panchayats.

The killing of Bir Singh is also mentioned. Bir Singh was a spiritual leader at the time with a large following. Bragging about it, the Khalsa Panchayats exclaimed they had committed Gurumar (killing a guru).

Although Jangnama does not explicitly posit arrogance and greed as the reason for the Khalsa’s collapse, it can be inferred, and their excessive lust for wealth and power contrasts with prior accounts of a Khalsa which Bhangu describes. Although they share a sovereign spirit those previous Sikhs and even re-establish a decentralized Misl-like system, the Khalsa within Jangnama generally seem to lack the righteousness that drove previous Sikhs. This is not to say seeking power and wealth was viewed negatively by Bhangu or others, in fact it was encouraged, but there was clearly higher moderation.

The Finest of the Khalsa Army

“Sham Singh, the hoary general, moved out from his headquarters; as also the Jallawalias, the heroes of many a legend. All the Rajput kings too descended from their mountain haunts — Those who had unblemished reputation as swordsmen. The Majhails and Doabias came marching, closing their ranks, as the Sandhawalias, on their haughty mounts. O Shah Muhammad! Also moved the fearsome Akal Regiment with flashing naked swords taken out from the scabbards.” (59)

Shah Muhammad describes the finest of the Sikh Empire’s army entering the battlefield against the British, a key figure being Sham Singh Attariwala, a general of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. These are the final accounts of a certain type of Khalsa Sikh, as many, including Sham Singh, would reject cowardice and die fighting on the battlefield.

Defeat (& Inner Death)

“When the fear had gripped them, in hushed tones did the young and inexperienced cavalryman talk: ‘Now that Feringhees have beaten us hollow, why not make good our escape at midnight? Had we taken to farming we would’ve had enough to eat. After all, whose sons are we but farmers?” (77)

Jangnama concludes with the Khalsa’s defeat. After thousands of casualties, the shock of finally experiencing loss dawns on the younger Singhs. What Muhammad describes can be seen as a death in their spirit. It dawns on these Sikhs that perhaps they should return to farming. In stark contrast to this passage, Koer Singh’s Gurbilas Patshahi Dasvi (1751), narrates the 10th Guru’s bold proclamation to his Sikhs, who were largely farmers, in the creation of the Khalsa (below).

ਕਿਰਸਾਨ ਜਗ ਮੈ ਭਏ ਰਾਜਾ

“I will embolden the farmers to become rulers of the world”

- Gurbilas Patshahi Dasvi, Koer Singh, 1751 (translation via Jvala Singh)

The contrast between the two passages illustrates a tragedy. As Guru Gobind Singh had once transformed a meek people into sovereigns, the Raj would eventually fall, and those sovereigns sought to return to the fields which their ancestors came from.

The Khalsa’s Revival

Sardar Kapur Singh (1909–1986) once explained that the Sikh religion sits uniquely amongst other world religions as it contains equally spiritual and political principles. It is not only that the spiritual doctrines inform Sikh governance, but that the Khalsa doctrine demands political sovereignty inherently. 18th and 19th century Sikhs understood this, and set themselves on a path towards Khalsa Raj despite facing heavy persecution for doing so. (Bhangu) This philosophy held continuously for 140 years, and Jangnama tells of an internal crisis and death that the Khalsa Sikhs would face after experiencing their empire crumble so abruptly.

Although it would be unfair to characterize all Sikhs since the mid 19th century as lacking the sovereign Khalsa identity, the political standing of Sikhs today generally exemplifies that a communal death occurred. While there are many factors why Sikhs of today have sat so long without sovereignty, a variable to address would be for an increase in Sikhs internalizing the Khalsa’s inherent sovereignty. This is likely happening as seen with the recent boom in re-discovery of early Khalsa texts amongst other avenues.

Jangnama, a powerful and sobering text from the Sikh Empire, is revealing in telling us precisely when the collective sovereign Khalsa spirit died and thus leaves the reader with a choice— a choice to carry on as is, or to fully revive the aspirations and march towards sovereignty as the 10th Guru ordained.

ਅਕਾਲ ਸਹਾਇ

Sources used:

Jangnama, Shah Muhammad (translation, P.K. Nijhawan)

Panth Prakash, Rattan Singh Bhangu, English (Volume 1, Volume 2)

Gurbilas Patshahi Dasvi, Koer Singh (translation, Jvala Singh)

THE SIKHS IN THE BRITISH CENSUS REPORTS, PUNJAB, Joginder Singh

🧊🧊